Live and Let Die is remembered for a number of things. It's the debut of Roger Moore in the role, and the best opening song of the franchise until Adele hits one out of the park. It's remembered as the only Bond film with the presence of straight-up magic, chiefly in the personage of Bond Girl Solitaire, a tarot-card reading fortune teller employed by the film's villain Mister Big. It's also remembered as the one with more black speaking roles in a Bond film before or since, and as the one where that means James Bond has to fight Harlem.

Well. He doesn't really. But let's start there.

Shortly after 007's arrival in New York, he takes a cab ride down through Harlem to follow a lead on a deceased British agent. His cab passes half a dozen people with speaking roles, and they're all reporting back to the mysterious Mr. Big. Even the cabbie is in on it. One of the things I noticed when I rewatched For Your Eyes Only was how paranoid the early goings of that film are. There's a sense in it that everyone--and everything--could spout murderous intent at any moment. Live and Let Die follows a similar approach but with an unsettling racial component. The Harlem of 1973 is as exotic territory for James Bond as the Soviet Union or Japan. It's filled with conspirators, a place where Bond sticks out like a sore thumb and everyone reports to the guy at the top. The paranoia on hand in Live and Let Die is specifically the paranoia of the white person in a majority black neighborhood, and with over forty years of hindsight, it's more than a little squick-worthy. Even when the film switches location to New Orleans, nearly every performer of color is part of Kananga's web of drug intrigue, to the point where a lounge singer can taunt our hero with a diagetic turn at the film's title song, then watch, along with every other patron in the establishment as Bond's chair recedes down a trap door, immediately to be replaced by staff with no one batting an eye.

Even before that cab ride, Bond's CIA driver is murdered by one of Big's henchmen (leading to the "immortal--if immortal can also be synonymous for aging really, really poorly--line: "Get me an APB on a White Pimpmobile!") in what is clearly meant to be a hit on Bond. The Cold Open features several murders, including one of a UN Ambassador and one of a British Agent. This mole is never explained. It is merely part of the architecture of dread surrounding Kananga and his operation. As another Bond antagonist would say thirty-five years later, "We have people everywhere." The problem with Live and Let Die is there's an unsettling idea of what all those people are meant to look like.

Of all the speaking roles given to black actors in this picture, only two are on the side of the proverbial angels. They're both CIA agents: Strutter, who is killed in what is probably the most theatrical way I've ever seen someone die in one of these movies (maybe ever), which is to say he is murdered by jazz funeral; and Rosie Carver, also CIA agent, though she's been turned by Kananga thanks in part to her terror of Island Voodoo. It's hard to tell if she's meant to be conning Bond this whole time or merely hilariously incompetent and bad at her job up until the point she betrays him. But, hey: Bond bangs her, so the movie can count itself as progressive.

Like most of Moore's tenure, Live and Let Die is a reactionary film, in more ways than just the obvious. The spy genre that Bond invented in 1962's Dr. No had crested in popularity, and Bond spent the Seventies and Eighties reacting to trends, be they kung fu films in The Man with The Golden Gun, Star Wars with Moonraker, or tech thrillers with A View to A Kill. Moore's debut in the role is no exception. Live and Let Die is a direct response to the wave of blaxploitation films that had taken America by storm.

I don't know what kind of business blaxploitation films were doing in Britain (I suspect none) but the Bond franchise has long had one eye on America, for obvious reasons. Bond, that square establishment figure, name-checks The Beatles in Goldfinger, and the cinematic landscape in America was quite a different one in 1973 than 1962. Some schoolbook history: the 1960's in America saw sweeping social changes and a growing social consciousness reflected in popular culture. White Americans fled the inner cities for cheap tract housing in the late Sixties, and black businesses flourished in their wake. Black Americans on the whole had a spending power they didn't possess in decades previous, and a desire to see themselves represented on film as more than tokens or stock characters. There had been films geared somewhat toward black audiences, but these were often heady issues-films. That was until 1970, and Cotton Comes to Harlem.

An escapist action film, Cotton Comes to Harlem was a smash hit. It was followed in 1971 by Shaft and Sweet Sweetback's Badasssss Song, the latter entirely self-produced for under a half million dollars. By the end of its run, Sweet Sweetback's Badasssss Song would make back twenty-four times its budget. Shaft's Big Score! and Super Fly followed in 1972, and by then dozens of films were being released independently and via the major studios featuring predominantly black casts and set in urban areas, frequently Harlem. A genre was born.

It wasn't without controversy. The lessening of some of the restrictions around what content could be shown in films meant these movies were often violent and frequently sexualized, and this eventually led to outcry over the fact that, among other things, white studio executives were making money off a fetishized vision of black urban life. Writing for Newsweek in 1972, president of the Los Angeles chapter of the NAACP Junius Griffin coined the portmanteau "blaxploitation," the banner that would stick with this new wave of film making for the rest of its Seventies heyday.

Enter James Bond. Live and Let Die is loosely based on the novel of the same name, Fleming's second in the Bond series. In the novel, Mister Big (real name Buonaparte Ignace Gallia, because subtlety) is selling salvaged pirate gold to finance Soviet spy operations in America. In the film, Big is the secret identity (false face and all) of Doctor Kananga, the President of a Caribbean island nation. In the film it's not pirate gold, but heroin, a billion dollars in 1973 money of it, ready to flood the market and depress prices and put those old timey gangsters running New York out of business.

The metaphor here is easy to draw. The landscape is shifting, and it makes some people uneasy. These people who don't look like you, suddenly it seems like they're everywhere. Suddenly they're more vocal. More than any other James Bond film, Live and Let Die is a more calculated response to a particular trend, rather than an attempt to merely copy its iconography. Blaxploitation movies featured criminals as their protagonists as often as they featured cops. Shown through another lens, Kananga would be the hero of this story.

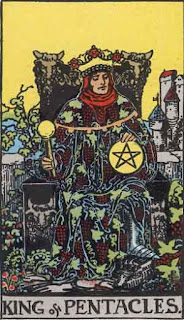

In the film, as in the book, Big/Kananga is assisted by Solitaire, a fortune teller able to predict the future and see present events at a remote distance, and if the racial politics of this film are unsettling to the modern eye, then boy howdy the sexual politics. Boy howdy. Solitaire's thing is cartomancy: she predicts the future using tarot cards, which leads to Bond inevitably drawing out "The Lovers" from her deck. Later on in the film, Bond buys seventy-eight identical tarot decks, fishes out "The Lovers" from each one and creates a stacked deck from which he asks this clairvoyant lady to pick a card. On any normal day this would be considered a dick move. At best it's frat-house level seduction game. At worst, he is exploiting either the fact that magic exists or, given his own skepticism, the beliefs of this young lady to get in her pants.

This is, to say the least, problematic. It's one thing for the films to adopt the idea that the ladies in them are pretty much always DTF, it's quite another for Bond to take his secret agent's talent for exploiting systems and apply it to this twenty-year-old girl. It's no better, really, than Kananga's exploitation of Rosie Carver's fear and superstition (which he helps along with mechanized statues and dolls and the like) to turn her against the CIA. What makes the whole business worse is that Solitaire is a virgin, and her predictive ability is tied to her virginity (for some reason) so James essentially humps the magic straight out of her.

The problem with Solitaire, and it's a problem that occurs pretty frequently within these films (particularly for ladies whose job description reads: "Bad Guy's Girlfriend"), is she's completely bereft of agency. Forget tarot, Solitaire is a chess piece. The sole saving grace of this entire plot line is that she's clearly unhappy working for Kananga and he's a dangerous dude and she fears for her life, but that doesn't make the film turning her lady area into a proxy battlefield between two dudes any more palatable. And that's before even taking in to account the film playing into centuries of imagery surrounding Virginal White Ladies and Sinister Black Men.

Ian Fleming was an accomplished racist. This isn't exactly news. The original copy of the novel Live and Let Die has a chapter title that cannot be repeated in polite company. The novel asserts also that the only reason Big became such a hot shot in the world of pirate gold and crime is down to mentorship by Soviet higher-ups. It's sort of a shame because Yaphet Kotto is such an enjoyable presence on screen. He's urbane and charming, and his youth--Kotto was thirty-four to Moore's forty-five--marks a change that feels as revitalizing to the franchise as Moore's casting does. In fact, the disparity in age between Bond and his antagonist has been flipped since Connery's own debut in Dr. No. There, Connery's Bond was just thirty-two, and the first of his antagonists, Joseph Wiseman's eponymous Evil Scientist, was forty-four.

The film, then, is an act of magic, as films are. Like Spectre forty-two years later, it takes an unease about the world and plants James Bond at the center of that unease, forcing him to navigate through it, that by his navigation do we see our own way out. But while Spectre's unease about the surveillance state is understandable and even laudable (if clumsy), it isn't possible to take the same reading of Live and Let Die, which seems to be all about assuring white people that they're still in charge. This of course ties right back to Fleming and his original conception of the character of James Bond. At the time of Bond's creation, the Sun had set on the British Empire. Its conquered territories were ceded back and it had diminished in importance next to the likes of the United States and the Soviet Union. The novels imagined James Bond and by extension the British Way of Doing Things as an integral part of that new political landscape. The Connery films are all about that narrative, of asserting Britain's continuing importance in this brave new world, reducing the Cold War belligerents to puppets of a vast criminal empire in the form of Ernst Blofeld's SPECTRE. By Live and Let Die, Connery and Blofeld are out, and the world is changing. To the extent that "keep Bond in business" is the desired outcome, then the spell worked, even if its component parts have aged badly.

If it sounds like I'm being harsh, well, I am. Live and Let Die is enjoyable for what it is, an un-self-conscious adventure film full of gadgets and gunfights, where a man walks across a bunch of alligators to escape a death trap. And while I don't believe the film makers intended for the finished product to turn out quite as racist as the one we got, it's not necessarily something I'd readily recommend to the uninitiated. The problem with this whole mess in that, in the end, it's not easy to dismiss it all as just a quaint throwback. Much of this baggage is still with us. The blaxploitation era would dwindle out around the late Seventies. There are fewer black-fronted films and absolutely fewer black-fronted television shows now in 2016 than there were when I was growing up as a teenager in the Nineties. The sort of "oh, it was a different time" dismissal doesn't quite work when serious Presidential contenders run on the back of racist and sexist rhetoric, and Hollywood professionals close ranks against the idea that hiring and casting attitudes should change.

Live and Let Die is, in the end, a very problematic film. But it has the great Roger Moore, a memorable villain, and I for one can't close the door completely on a movie with a murderous jazz funeral.

|

| Proofreading and tarot consultation provided by my beautiful, long-suffering wife Anne. |

No comments:

Post a Comment